Stalking and surveillance

Topic last updated: | See what’s been updated

Key findings

Violence encompasses a wide range of behaviours and harms, including stalking, surveillance, and other harassing and abusive behaviours. These behaviours can occur in both family and non-family settings.

The widespread availability of technology and the ease of maintaining anonymity online has increased the opportunity for stalking and surveillance in recent years. Perpetrators may misuse devices, accounts, software or platforms to control, abuse and track victim-survivors (DSS 2022). Irrespective of whether these behaviours are experienced in-person or online, they can have significant implications for personal safety, productivity and mental wellbeing.

This topic page discusses the prevalence and characteristics of stalking and surveillance, particularly with the FDV context. It also explores how technology has been misused to support the perpetration of these behaviours.

What is stalking and surveillance?

Stalking is a pattern of unwanted behaviours aimed at causing fear or distress and reducing the victim’s autonomy and sense of security, which is often considered a form of emotional abuse (NSW Police Force 2023; SPARC 2023; ABS 2023). It can involve a range of different behaviours and is a crime in all states and territories of Australia (see Box 1). Stalking often includes surveillance behaviours that provide information on the victim’s movements and activities to perpetrators (Maher et al. 2017).

In Australia, State and Territory governments are responsible for making and enforcing criminal laws related to stalking. As such the definition of stalking can vary slightly across states and territories. However, in most states, a person has perpetrated stalking if, on at least 2 occasions, they conduct one or more of the following actions with the intent to cause harm or apprehension:

- follow or approach the other person

- loiter near, watch, approach or enter a place where the other person resides, works or visits

- keep the other person under surveillance

- interfere with property in the possession of the other person

- give or send offensive material to the other person or leaves offensive material where it is likely to be found by, given to or brought to the attention of the other person

- telephone or otherwise contact the other person

- act covertly in a manner that could reasonably be expected to arouse apprehension or fear in the other person

- engage in conduct amounting to intimidation, harassment or molestation of the other person.

For information on legal and police responses to family, domestic and sexual violence, please refer to the Legal systems, FDV reported to police and Sexual assault reported to police topic pages.

Source: AustLII 2023a, 2023b, 2023c, 2023d, 2023e, 2023f, 2023g; Department of Justice 2017

Increasingly, mobile and digital technologies are utilised to conduct stalking and associated surveillance behaviours. When stalking and surveillance are conducted via technology, they are considered technology-facilitated abuse (TFA) (see Box 2).

Technology-facilitated abuse (TFA) is a broad term encompassing any form of abuse that utilises mobile and digital technologies, which can include a wide range of behaviours such as:

- Monitoring and stalking the whereabouts and movements of the victim in real time.

- Monitoring the victim’s internet use.

- Remotely accessing and controlling contents on the victim’s digital device.

- Repeatedly sending abusive or threatening messages to the victim or the victim’s friends and family.

- Image-based abuse (non-consensual sharing of intimate images of the victim).

- Publishing private and identifying information of the victim.

Source: Powell et al. 2022; AIJA 2022; Woodlock 2015

Stalking can occur as part of family and domestic violence (FDV), with current and previous intimate partners often identified as some of the most common perpetrators (ABS 2017; Smith et al. 2022; Victoria State Government 2023). Stalking is also a risk factor for other forms of FDV, such as physical violence and intimate partner homicide (Mechanic et al. 2000; Spencer and Stith 2018).

Some perpetrators conduct stalking and surveillance repeatedly over time to establish and maintain control over the other person. These behaviours may be used as part of coercive control. Please refer to the Coercive control topic page for more information.

Some stalking and surveillance behaviours are forms of sexual harassment, such as repeatedly sending messages with sexual content. Please refer to the Sexual violence topic page for more information on sexual harassment.

What do we know?

As with other forms of gender-based violence, the majority of victims of stalking and surveillance, are women. This can partially be attributed to gender-based power inequalities, rigid gender norms and gender-based discrimination.

The National Community Attitudes towards Violence against Women Survey (NCAS) is a nationally representative survey that measures community understanding and attitudes towards violence against women and gender inequality. The 2021 NCAS found that most respondents (89%) recognised in-person stalking as always or usually violence against women, but less respondents (83%) recognised electronic stalking as always or usually a form of violence. Almost 9 in 10 (89%) respondents were aware it is a criminal offence to share an intimate picture of an ex-partner on social media without their consent (Coumarelos et al. 2023).

A study on community attitudes towards stalking in Victoria found that men were more likely to strongly endorse beliefs and attitudes that minimise the severity of stalking, normalise the behaviour as romantic and assign blame to the victim (McKeon and McEwan 2014).

Risk factors for stalking and surveillance

There is limited research on the risk factors for stalking and surveillance victimisation and perpetration. However, studies suggest common risk factors associated with stalking victimisation include having an ex-intimate relationship with the perpetrator, receiving explicit threats and property damage by the perpetrator (Thompson et al. 2013; McEwan et al. 2016). In cases of co-parenting, interactions relating to the child (such as handover) may provide opportunities for stalking and surveillance perpetration. This can involve installing or checking tracking and surveillance devices, or manipulating the child to facilitate abuse (such as sharing the victim’s password) (Dragiewicz et al. 2022).

A study on 700 stalkers from Queensland identified sociocultural predispositions (such as violent family members and friends), psychological traits (such as need for control and narcissism), history of violence, revenge motives, triggering events, and illicit drug and alcohol use as risk factors for perpetrating severe stalking violence (Thompson et al. 2013).

Co-occurrence of stalking and surveillance with intimate partner violence

Stalking often co-occurs with intimate partner violence and can be used to exert power and control during and/or after an abusive relationship. Studies suggest that abusive partners who stalk are more likely to physically injure, threaten, verbally abuse and sexually assault the victim, compared with abusive partners who do not stalk (SPARC 2018).

Intimate partner stalkers are more likely to use the widest range of stalking behaviours, contact and approach victims more frequently, escalate the frequency and severity of pursuit, and follow through on threats of violence, compared with stalkers who are not intimate partners (SPARC 2018).

Co-occurrence of stalking and surveillance with sexual violence

Sexual violence can be part of a stalker’s pattern of behaviour. Sexually violent stalking behaviours commonly fall under four categories:

- Surveillance (e.g. following and monitoring a victim while planning or after committing sexual assault).

- Life invasion (e.g. repeated unwanted communication of a sexual nature, spreading sexual rumours or publicly humiliating with information about sexual activity).

- Intimidation (e.g. threatening sexual violence, blackmailing the victim in exchange for sexual activity, images or videos).

- Interference through sabotage or attack (e.g. sexual assault, in-person or image-based indecent exposure) (SPARC 2022).

What data are available to report on stalking and surveillance?

Data on the extent and nature of stalking come from national surveys, some of which focus specifically on TFA behaviours. The surveys used throughout this section include:

- ABS Personal Safety Survey 2016 and 2021-22 – collected information on experiences of stalking since the age of 15 among 21,200 and 11,900 people aged 18 years and over in Australia, respectively (ABS 2023).

- ANROWS Technology-facilitated abuse reports – examined TFA victimisation and perpetration among 4,600 respondents aged 18 years and over in Australia, which included online harassing, monitoring and/or controlling behaviours. The survey used random probability-based sampling methods and weighting to allow results to be generalisable to the adult population in Australia (Powell et al. 2022).

- eSafety Commissioner Negative online experiences 2022 findings – examined adults’ online experiences, including monitoring and harassment behaviours, among 4,800 respondents aged 18-65 in Australia. The survey used quota sampling and was weighted to ABS population data to allow results to be generalisable to the adult population in Australia (eSafety Commissioner 2023a).

Some administrative data from the ABS Recorded Crime – Offenders collection are available to report on the perpetrators of stalking and surveillance, which include statistics about offenders proceeded against by police (ABS 2024b).

For more information about these data sources, please see Data sources and technical notes.

What do the data tell us?

How many people have experienced stalking and surveillance?

Women are more likely to experience stalking than men

-

1 in 5 women

over 1 in 15 men

in 2021–22 had experienced stalking since the age of 15

Source: ABS Personal Safety Survey

The 2021–22 PSS found that 2.7 million people aged 18 and over have experienced stalking since the age of 15. One in 5 (20% or 2.0 million) women and over 1 in 15 (6.8% or 653,000) men have experienced stalking since the age of 15 (ABS 2023).

In the 12 months before the survey, 3.4% (or 338,000) of women and 0.6% (or 60,600) of men had experienced stalking. However, the 12-month data for men has a relative standard error between 25% and 50% and should be interpreted with caution (ABS 2023).

Monitoring and controlling behaviour is the most common type of TFA

-

Half (51%) of respondents in 2022 had experienced technology-facilitated abuse in their lifetime

Source: ANROWS Technology-Facilitated Abuse Survey

The ANROWS 2022 study on TFA found that half (51%) of the respondents had experienced at least one TFA behaviour in their lifetime (see Data sources and technical notes for behaviours included in the study). The most common type of TFA experienced was monitoring and controlling behaviours, with around 1 in 3 (34%) respondents having experienced this type of TFA. This was true for both women and men (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Types of TFA ever experienced, by gender, 2022

| Behaviour | Women | Men | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional abuse and threats | 31.2% | 29.8% | 30.6% |

| Sexual and image-based abuse | 28.9% | 19.3% | 24.6% |

| Monitoring and controlling behaviours | 32.6% | 35.0% | 33.7% |

| Harassing behaviours | 24.7% | 29.0% | 26.7% |

Note:

- Total includes men and women only. Analyses by ANROWS excluded 21 respondents who were transgender, non-binary, intersex and/or another gender identity and 3 respondents who did not disclose a gender identity.

For more information, see Data sources and technical notes.

Source:

ANROWS Technology-Facilitated Abuse Survey

|

Data source overview

Preliminary findings from the Australian eSafety Commissioner’s 2022 survey on negative online experiences also highlight the use of technology in the perpetration of stalking and surveillance. Among the 4,800 respondents:

- 18% reported having their location tracked electronically without consent

- 16% reported receiving online threats of in-person harm or abuse (eSafety Commissioner 2023a).

Perpetrators of stalking and surveillance

Women are more likely to be stalked by a man than a woman

The 2021-22 PSS showed that among adults that have experienced stalking since the age of 15:

- more than 9 in 10 (94% or 1.9 million) women were stalked by a male

- men were equally likely to be stalked by a male or by a female (ABS 2023).

The ANROWS study on TFA found that the most common type of TFA perpetrated was monitoring and controlling behaviours, with around 1 in 5 (19%) respondents having perpetrated this type of TFA. While more than 3 in 5 (62% or 1,400) victim-survivors of all TFA reported the most recent perpetrator was a man, more women (22%) than men (16%) overall reported that they were perpetrators of monitoring and controlling behaviours. For all other types of TFA, more men reported being perpetrators than women (Powell et al. 2022) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Types of TFA ever perpetrated, by gender, 2022

| Behaviour | Women | Men | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional abuse and threats | 5.1% | 7.2% | 6.0% |

| Sexual and image-based abuse | 2.3% | 6.5% | 4.2% |

| Monitoring and controlling behaviours | 22.1% | 16.2% | 19.4% |

| Harassing behaviours | 6.5% | 10.0% | 8.1% |

Note:

- Total includes men and women only. Analyses by ANROWS excluded 21 respondents who were transgender, non-binary, intersex and/or another gender identity and 3 respondents who did not disclose a gender identity.

For more information, see Data sources and technical notes.

Source:

ANROWS Technology-Facilitated Abuse Survey

|

Data source overview

Women and men are more likely to experience stalking from someone they know

The latest available data for reporting on relationship to the perpetrator is from the 2016 PSS. The 2016 PSS found that, for women who had experienced stalking since the age of 15, the most recent stalking episode by a male was perpetrated by:

- a known person for 3 in 4 (75% or 1.1 million) women, with 3 in 10 (30% or 448,000) of these women stalked by a current or previous partner

- a stranger for 1 in 4 (25% or 365,000) women (ABS 2017).

For men who had experienced stalking since the age of 15, the most recent stalking episode by a female was perpetrated by a known person for more than 9 in 10 (95% or 286,000) men. The perpetrator was a current or previous partner for 2 in 5 (41% or 124,000) of these men; however the proportion should be interpreted with caution due to sampling errors (ABS 2017).

For men, the perpetrator of the most recent stalking episode by a male was about equally likely to be a stranger (151,000) as to be a known person (170,000) (ABS 2017).

Loitering or following is the most common stalking behaviour experienced by women from current or previous intimate partners

For women whose current or previous partner had recently stalked them:

- 2 in 3 (68% or 450,000) had experienced loitering by the perpetrator in locations such as the home, workplace, school, education facility, places of leisure or at social activities

- 3 in 5 (61% or 404,000) had experienced unwanted contact by phone, postal mail, email, text messages or social media

- 2 in 5 (44% or 290,000) were followed or watched, either in person or electronically (AIHW 2019; ABS 2018).

For men whose current or previous female partner had recently stalked them, about half (52% or 112,000) had experienced loitering and 4 in 10 (40% or 84,100) were followed or watched in person or electronically (AIHW 2019; ABS 2018).

What are the responses to stalking and surveillance?

Responses to abuse generally comprise a mix of formal responses and informal responses. Examples of formal responses include police, legal services, and other support services such as 1800RESPECT, eSafety Commissioner and Lifeline; while informal responses can include support from family and friends (see How do people respond to FDSV?).

Although it is important to understand the usage and effectiveness of these services, there is currently limited national data on the responses to stalking and surveillance in Australia.

Police and justice system

Personal safety intervention order (PSIO) is a court order to protect a person, their children and their property from another person’s behaviour. PSIOs are also known as restraining or apprehended violence orders in some states and territories.

Police and the justice system are a major part of the formal response to stalking and surveillance. The police can assist a stalking victim with applying for a personal safety intervention order, file criminal charges where appropriate and refer victims to support services (Victorian Law Reform Commission 2021).

Men are more likely to be offenders of FDV-related stalking than women

The ABS Recorded Crime – Offenders data collection recorded 6,800 offenders of family and domestic violence-related stalking in 2022–23. Among people aged 10 and over, males had a higher offending rate for FDV-related stalking (49 per 100,000 males, or 5,600), compared with 9.9 per 100,000 females (or 1,200) (ABS 2024a).

Numbers and rates for stalking may be overstated as New South Wales legislation does not contain discrete offences for stalking, intimidation and harassment – these offences are all coded and reported as ‘stalking’. See Data sources and technical notes for more information.

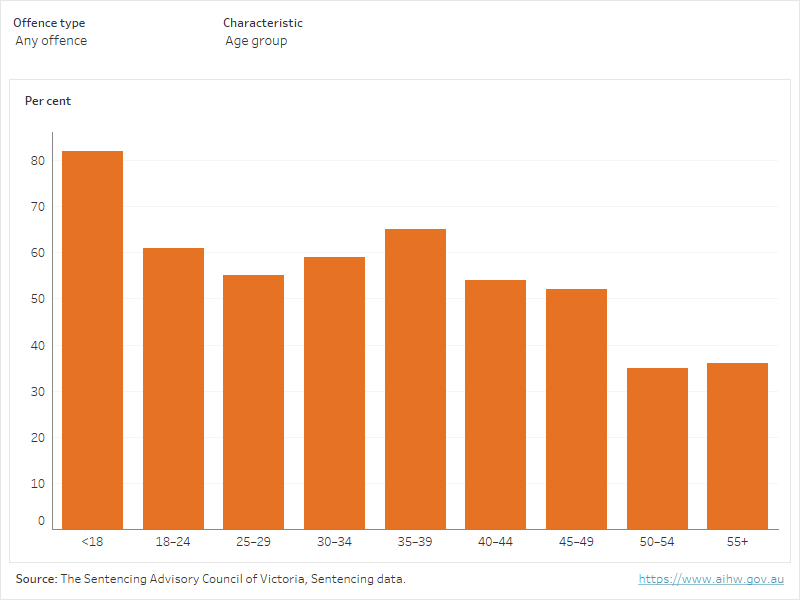

Reoffending among stalking offenders

The Sentencing Advisory Council of Victoria found that more than half (56%) of people sentenced for stalking offences in 2015 or 2016 had been sentenced again (for any offence) within four years. One in 4 (25%) were sentenced for breach of a family violence safety notice (FVSN) or intervention order (FVIO), and almost 1 in 5 (18%) had been sentenced for a violent offence (Chalton et al. 2022) (see the Glossary for definitions). The Council also found that:

- Family violence-related stalking offenders were more likely to reoffend within four years than non-family violence-related offenders, except in the case of reoffences involving breach of a personal safety intervention order (PSIO)

- Male stalking offenders were more likely to reoffend within four years than female stalking offenders, except in the case of reoffences involving breach of a PSIO (Chalton et al. 2022) (Figure 3).

Multiple behaviours can occur within one stalking episode and over an extended time period. It is unknown whether the subsequent offences occurred as part of a stalking episode for the same victim or if they were perpetrated against the same or different victim. Please see the Glossary for definitions of FVSN, FVIO and PSIO.

Figure 3: Proportion of stalking offenders sentenced at least once within four years of an initial stalking sentence, by offence type and offender characteristics, Victoria

Figure 3 shows the proportion of stalkers in Victoria sentenced at least once within 4 years after an initial stalking sentence in 2015-16, by offence types and offender characteristics.

Online safety grants program

The Office of the eSafety Commissioner is an independent government agency committed to safeguarding people at risk of online harms and promoting safe and positive online experiences. The agency leads various online safety grant programs in response to TFA, such as the Preventing Tech-based Abuse of Women Grants Program (2023-2028) that funds initiatives with the goal of preventing gender-based TFA (eSafety Commissioner 2023b).

What are the impacts of stalking?

There is a lack of national data on the impacts of stalking, but existing research suggests that stalking behaviours contribute to negative outcomes in physical health, mental health, social life, economic and financial circumstances, and even death. Please refer to the Health outcomes, Economic and financial impacts and Domestic homicide topic pages for more information on impacts and outcomes of family, domestic and sexual violence.

Health impacts

Stalking is associated with harmful effects on the victim-survivor’s physical health, such as escalating to physical and sexual violence, excessive fatigue, chronic sleep disturbance and disturbances to appetite (McEwan et al. 2007; Pathé and Mullen 1997; Dreßing et al. 2020).

Stalking can also contribute to a deterioration in the victim-survivor’s mental health, and these impacts are often complex and long-lasting (Korkodeilou 2016). They can include increased levels of anxiety, overwhelming sense of powerlessness, depressive disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicidal ideation or attempted suicide (Pathé and Mullen 1997; Dreßing et al. 2020).

Disruptions to social life

Stalking can also lead to disruptions to the victim-survivor’s social life. Victim-survivors may restrict social outings, avoid certain places or people, change contact details, change or cease employment, or even relocate to a new home, which commonly contribute to isolation from social circles (Pathé and Mullen 1997; McEwan et al. 2007; Korkodeilou 2016). Strains on interpersonal relationships can also occur when victim-survivors develop trust issues as a result of stalking or feel they are not taken seriously or supported by people around them (Korkodeilou 2016).

Economic and financial burden

Other than the cost of relocating and changing or ceasing employment, stalking can contribute to economic and financial burden through reducing the productivity of the victim-survivor and people known to the victim-survivor, legal costs, health treatment costs, and costs of security devices like CCTV cameras and panic alarms (Dreßing et al. 2020; Pathé and Mullen 1997; Korkodeilou 2016).

Homicide

A report on intimate partner violence homicides published by ANROWS found that 2 in 5 (42%) female victims in intimate partner homicide had been stalked by the male perpetrator (ADFVDRN and ANROWS 2022).

Has it changed over time?

The PSS shows that the 12-month prevalence rate of stalking for women was similar between 2021–22 (3.4% or 338,000) and 2016 (3.1% or 228,000) (ABS 2023; ABS 2017). Data on changes over time for men is excluded here due to sampling errors impacting data reliability (ABS 2017).

Offender rate for FDV-related stalking has increased for men and women

Meanwhile, the ABS Recorded Crime – Offenders data collection recorded an increase in the offender rate for FDV-related stalking:

- For men, the offender rate increased from 38 per 100,000 males in 2019–20 to 49 per 100,000 males in 2022–23.

- For women, the offender rate increased from 6.1 per 100,000 females in 2019–20 to 9.9 per 100,000 females in 2022-23 (ABS 2024a).

Impacts of COVID-19

There is limited national data on the impacts of COVID-19 on the extent and nature of stalking and surveillance; however, some data for Victoria are available. In Victoria, the number of police-recorded stalking offences increased by 17% from 2019 to 2020, with a noticeable shift from in-person to online stalking behaviours during COVID-19. The number of stalking offences sentenced in this period decreased, while the imprisonment rate for stalking charges almost doubled. This is largely due to courts prioritising cases where a defendant was either on remand or likely to receive imprisonment during the pandemic (Chalton et al. 2022).

Is it the same for everyone?

Some population groups may be more affected by stalking and surveillance due to unique, and in some cases, multiple forms of disadvantage and discrimination. There is currently a lack of data on how different population groups experience stalking and surveillance; however, these data are important for understanding how the extent and nature of abuse can vary, and strengthening responses for groups at higher risk.

For information on the experiences of FDSV among specific population groups more broadly, see Population groups.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2011) 029 Other acts intended to cause injury, ABS website, accessed 14 June 2023.

ABS (2017) Personal safety, Australia, 2016, ABS website, accessed 27 April 2023.

ABS (2018) Personal Safety Survey, 2016, TableBuilder, ABS website, accessed 27 April 2023.

ABS (2023) Personal Safety, Australia, ABS website, accessed 11 May 2023.

ABS (2024a) Recorded Crime – Offenders, ABS website, accessed 23 February 2024.

ABS (2024b) Recorded Crime – Offenders methodology, ABS website, accessed 23 February 2024.

ADFVDRN (Australian Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Network) and ANROWS (Australia's National Research Organisation for Women's Safety) (2022) Australian Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Network Data Report: Intimate partner violence homicides 2010–2018 (2nd ed.; Research report 03/2022), ANROWS, accessed 10 May 2023.

AIHW (2019) Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia: continuing the national story 2019, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 24 August 2023.

AIJA (Australasian Institute of Judicial Administration) (2022) ‘Following, harassing and monitoring’, National Domestic and Family Violence Bench Book, AIJA website, accessed 27 April 2023.

AustLII (Australasian Legal Information Institute) (2023a) ‘Crimes Act 1900 – Sect 35’, Australian Capital Territory Current Acts, AustLII website, accessed 20 June 2023.

AustLII (2023b) ‘Crimes Act 1958 – Sect 21A’, Victorian Current Acts, AustLII website, accessed 20 June 2023.

AustLII (2023c) ‘Criminal Code 1899 – Sect 359B, Queensland Consolidated Acts, AustLII website, accessed 20 June 2023.

AustLII (2023d) ‘Criminal Code 1924 – Sect 192’, Tasmanian Consolidated Acts, AustLII website, accessed 20 June 2023.

AustLII (2023e) ‘Criminal Law Consolidation Act 1935 – Sect 19AA’, South Australian Current Acts, AustLII website, accessed 20 June 2023.

AustLII (2023f) ‘Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007 – Sect 13’, New South Wales Consolidated Acts, AustLII website, accessed 20 June 2023.

AustLII (2023g) ‘Criminal Code Act 1983 – Schedule 1’, Northern Territory Consolidated Acts, AustLII website, accessed 20 June 2023.

Chalton A, McGorrery P, Bathy Z, Dallimore D, Schollum P and Simu O (2022) Sentencing stalking in Victoria, Sentencing Advisory Council, accessed 27 April 2023.

Coumarelos C, Weeks N, Bernstein S, Roberts N, Honey N, Minter K and Carlisle E (2023) Attitudes matter: the 2021 National Community Attitudes towards Violence against Women Survey (NCAS), findings for Australia, ANROWS, accessed 12 May 2023.

Department of Justice (2017) Criminal Code Act Compilation Act 1913, Department of Justice, Government of Western Australia, accessed 20 June 2023.

Dragiewicz M, O’Leary P, Ackerman J, Bond C, Foo E, Young A and Reid C (2020) Children and technology-facilitated abuse in domestic and family violence situations: full report, eSafety Commissioner, accessed 28 April 2023.

Dragiewicz M, Woodlock D, Salter M and Harris B (2022) ‘What’s Mum’s password?’: Australian mothers’ perceptions of children’s involvement in technology-facilitated coercive control’, Journal of Family Violence, 37(1):137-149, doi:10.1007/s10896-021-00283-4.

Dreßing H, Gass P, Schultz K and Kuehner C (2020) ‘The prevalence and effects of stalking’, Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 117(20):347-353, doi:10.3238/arztebl.2020.0347.

eSafety Commissioner (2023a) Australians’ negative online experiences 2022, eSafety Commissioner, Australian Government, accessed 19 June 2023.

eSafety Commissioner (2023b) eSafety grants, Australian Government, accessed 9 May 2023.

Korkodeilou J (2016) ‘”No place to hide”’: stalking victimisation and its psycho-social effects’, International Review of Victimology, 23(1):17-32, doi:10.1177/0269758016661608.

Maher JM, McCulloch J and Fitz-Gibbon K (2017) ‘New forms of gendered surveillance? Intersections of technology and family violence’, Gender, Technology and Violence, 1st edn, Routledge, Abingdon and New York.

McEwan TE, Daffern M, MacKenzie RD and Ogloff JRP (2016) ‘Risk factors for stalking violence, persistence, and recurrence’, The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 28(1):38-56, doi:10.1080/14789949.2016.1247188.

McEwan T, Mullen PE and Purcell R (2007) 'Identifying risk factors in stalking: a review of current research’, International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 30(1):1-9, doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2006.03.005.

McKeon B and McEwan TE (2014) ‘”It’s not really stalking if you know the person”: measuring community attitudes that normalise, justify and minimise stalking’, Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 22(2):1-16, doi:10.1080/13218719.2014.945637.

Mechanic MB, Weaver TL and Resick PA (2000) ‘Intimate partner violence and stalking behavior: exploration of patterns and correlates in a sample of acutely battered women’, Violence and Victims, 15(1):55-72, doi:10.1891/0886-6708.15.1.55.

NSW Police Force (2023) What is stalking?, NSW Government, accessed 28 April 2023.

Pathé M and Mullen PE (1997) ‘The impact of stalkers on their victims’, The British Journal of Psychiatry, 170(1):12-17, doi:10.1192/bjp.170.1.12.

Pittaro M (2007) ‘Cyber stalking: an analysis of online harassment and intimidation’, International Journal of Cyber Criminology, 1(2):180-197, doi:10.5281/zenodo.18794

Powell A, Flynn A and Hindes S (2022) Technology-facilitated abuse: national survey of Australian adults’ experiences, ANROWS, accessed 28 April 2023.

Ramsey S, Kim M and Fitzgerald J (2022) Trends in domestic violence-related stalking and intimidation offences in the criminal justice system: 2012 to 2021, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, accessed 28 April 2023.

Smith SG, Basile KC and Kresnow M (2022) The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2016/2017 report on stalking, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, accessed 19 June 2023.

SPARC (Stalking Prevention, Awareness, and Resource Center) (2018) Stalking and intimate partner violence: fact sheet, SPARC website, accessed 25 July 2023.

SPARC (2022) Stalking and sexual violence: fact sheet, SPARC website, accessed 25 July 2023.

SPARC (2023) What is stalking? Definition and FAQs, SPARC website, accessed 15 June 2023.

Spencer CM and Stith SM (2020) ‘Risk factors for male perpetration and female victimization of intimate partner homicide: a meta-analysis’, Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 21(3),527-540, doi:10.1177/1524838018781101.

Thompson CM, Dennison SM and Stewart AL (2013) ‘Are different risk factors associated with moderate and severe stalking violence?: Examining factors from the integrated theoretical model of stalking violence’, Criminal Justice and Behavior, 40(8), doi:10.1177/0093854813489955.

Victorian Law Reform Commission (2021) 3. Understanding and responding to stalking, Stalking: Consultation Paper (html), Victorian Law Reform Commission, accessed 25 July 2023.

WHO (World Health Organisation) & London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (2010) Preventing intimate partner and sexual violence against women: taking action and generating evidence, WHO website, accessed 28 April 2023.

Wolbers H, Boxall H, Long C and Gunnoo A (2022) Sexual harassment, aggression and violence victimisation among mobile dating app and website users in Australia, Australian Institute of Criminology, accessed 10 May 2023.

Woodlock D (2015) ReCharge: Women’s technology safety, legal resources, research & training, Women’s Legal Service NSW, Domestic Violence Resource Centre Victoria and WESNET, accessed 16 June 2023.

- Previous page Child sexual abuse

- Next page Modern slavery